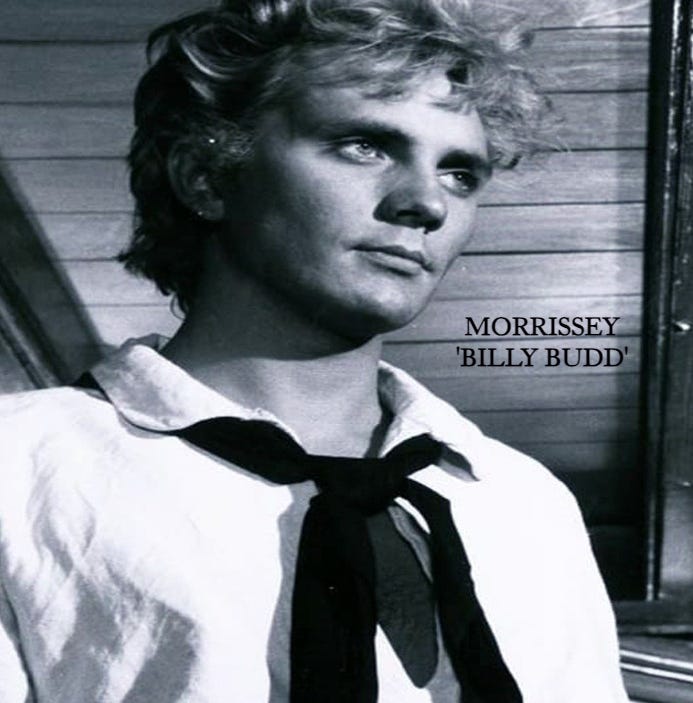

‘Billy Budd’ is the third track on Morrissey’s 1994 Vauxhall and I studio album. The song's title is taken from a 1962 film by Peter Ustinov, which of course is itself an adaptation of Herman Melville's novella, Billy Budd, Sailor (An Inside Narrative). In both the movie and the novella, Billy Budd is an innocent, naive seaman in the British Navy in 1797. Billy's good looks and charisma make him popular with the crew of the ship, the HMS Bellipotent . While initially intrigued by Billy, the ship's sadistic master-at-arms, John Claggart, becomes enraged at him and then falsely charges Billy with conspiracy to mutiny. Upon hearing this baseless accusation, a stunned, speechless Billy lashes out and accidentally kills Claggart - an act that leads to his court-martial and execution.

The handsomeness of Billy Budd is a central point in Melville's novella, where he is described by Captain Vere as "the young fellow who seems so popular with the men—Billy, the Handsome Sailor," has led to interpretations of an underlying homoerotic theme.

In fact, there have been interpretations of the interrelationships between Billy, Claggart and Captain Vere as being representative of male homosexual desire, with Claggart's trumped-up charge of mutiny, and Captain Vere's expedited trial (followed by Billy's immediate execution by hanging) symptomatic of societal prohibition against this desire. It is interesting to note that Claggart's character is described in the novel as possessing a "natural depravity," which can (possibly) be interpreted as a sort of 19th century "code" denoting a homosexual.

The following exchange between Billy Budd and master-at-arms Claggart provides a window into the homoerotic paradigm detected in the novel:

Billy Budd: Would it be alright if I stayed topside a little bit to watch the water?

Claggert: I suppose a handsome sailor may do many things forbidden to his mess-mates.

Billy Budd: Sea's calm tonight, i'nt it? Calm and peaceful.

Claggert: You've made a good impression on the captain, Billy Budd. You have a pleasant way with you.

Billy Budd: Oh, thank you sir.

Claggert: If you wish to make a good impression with me too however, you will need to curb your tongue.

Billy Budd: Now, sir?

Claggert: Not now. Can it be that you really don't understand my words? Is it ignorance or irony that makes you speak so simply?

Billy Budd: It must be ignorance, sir — because I don't understand the other word.

Claggert: The sea is calm you said. Peaceful. Calm above, but below a world of gliding monsters preying on their fellows. Murderers, all of them. Only the strongest teeth survive. And who's to tell me it's any different here on board, or yonder — on dry land? You knew my reputation, and yet you dared to speak what you called the truth. Why?

Billy Budd: I know some of the men are fearful of you, hate you. But I told them — you can't be as they think you are.

Claggert: Why not, pray?

Billy Budd: No man can take pleasure in cruelty.

Claggert: No? Tell me, do you fear the lash?

Billy Budd: [nods] Aye.

Claggert: And will you speak the truth again?

Billy Budd: I'm on my honor, sir. If the captain asks—

Claggert: [laughs grimly — and Budd joins in laughing] Why are you laughing boy?

Billy Budd: Laughter's good, sir. And it's good to hear you laugh.

Claggert: Laughter's good? Even the laughter of fools aimed at nothing?

Billy Budd: No, sir, you wouldn't laugh at nothing.

Claggert: What was I laughing at then?

Billy Budd: I don't know sir, but I think you were laughing at yourself.

Claggert: [puzzled and disturbed] Why would I laugh at myself?

Billy Budd: There's time when all men do — men as you would call men. They make mistakes and behave like fools.

Claggert: They do. Tell me in all ignorance do you dare understand me, then?

Billy Budd: [nods] I think so, sir.

Claggert: Why did Jenkins die?

Billy Budd: You did not wish his death.

Claggert: No, I did not.

Billy Budd: You didn't even hate him. I think that sometimes you hate yourself. I was thinking, sir, the nights are lonely. Perhaps I could talk with you between watches when you've nothing else to do.

Claggert: Lonely. What do you know of loneliness?

Billy Budd: Them's alone that want to be.

Claggert: Nights are long — conversation helps pass the time.

Billy Budd: Can I talk to you again, then? It would mean a lot to me.

Claggert: Perhaps to me, too. [his expression suddenly turns suspicious and sours] Oh, no. You would charm me too, huh? Get away.

Billy Budd: Sir?

Claggert: Get — away!

The lyrics of 'Billy Budd' speaks to a relationship that has seemingly gone awry: "Everyone's laughing / Since I took up with you / Things have been bad" (especially for the singer, having been turned down for a job due to his relationship with the subject). The singer wants the subject (and himself?) to be free from the controversy and problems their relationship has wrought, rhetorically stating that he'd go so far as to sacrifice his legs if necessary to be freed from the shackles of their partnership:

"I said, Billy Budd/I would happily lose/Both of my legs/I would lose both of my legs/Oh, if it meant you could be free"

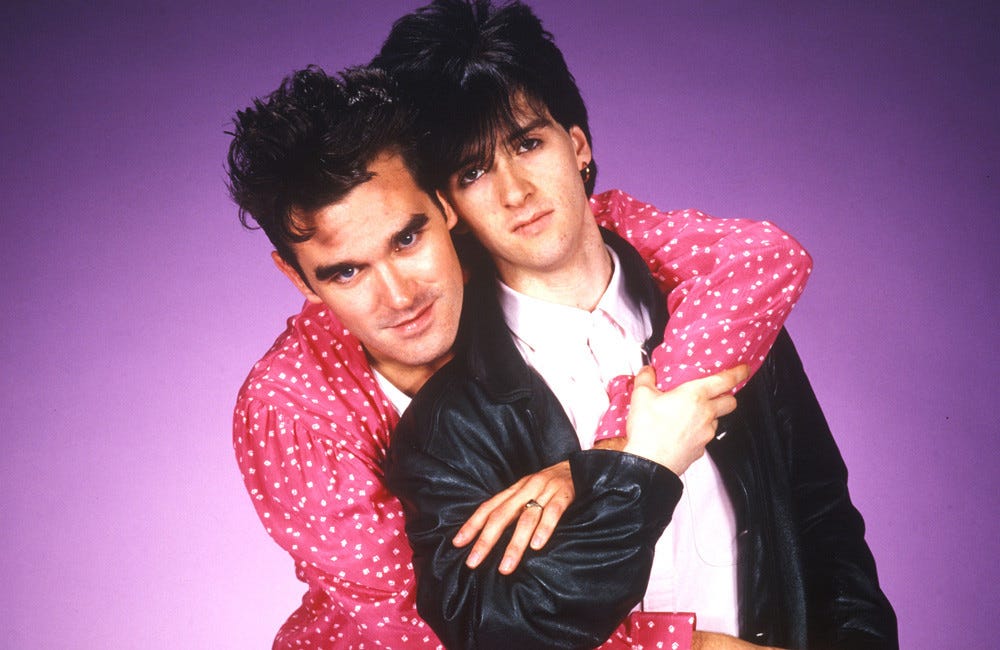

Many speculate that 'Billy Budd' is in fact about Morrissey’s relationship with Johnny Marr, especially because of the reference to having taken up “with you” for 12 years on.

This time reference happens to coincide with when Morrissey and Marr had begun their professional relationship (in 1982) at the time the song was released. Interestingly, on page 206 of Morrissey's Autobiography, he makes a direct reference to Melville when describing an incident involving his stumbling upon Johnny Marr working with singer Bryan Ferry in the studio on one of the latter's songs: "I walk into the room and all three freeze with Colonel Mustard unease [...] the Smiths battleship springs its first mutinous leak, with John Porter as sly Captain Bligh, and Johnny as the always-innocent young cabin-boy, hoping old Moby Dick will use his tune." Then there is the ironic (and astonishing) fact that Herman Melville wrote a volume of poetry titled 'John Marr and Other Sailors'.

While this can be chalked up to coincidence, it does leave Morrissey's use of a Melville character as both the song's title and subject open to more than just idle speculation.

Morrissey samples from David Lean's 1948 film Oliver Twist a bit of dialogue - “Don't leave us in the dark!” - at the very end of the song.

In the film these words are uttered by actor Anthony Newley (playing the Artful Dodger) to Robert Newton’s character (the brutal Bill Sykes) as the latter leaves Fagin’s gang in a darkened room as the police close in.

The use of this very specific piece of dialogue could either be an attempt to render the true meaning of the song inscrutable, or (more likely) it may be a sort of final plea from Morrissey to Marr - seeking a reply that might bring about closure of some kind to the long running issue of their fractured relationship. Given Morrissey’s propensity for ambiguity and literary license, the author believes that in fact it is the latter. Unfortunately, it would appear that Marr never responded.