Bengali In Platforms

The convoluted genesis of the song that sparked the left's war on Morrissey

August 1987 was a sort of period of limbo after the de facto dissolution of the Smiths, but before the beginning of Morrissey’s career as a solo artist. It was at this time that Morrissey extended an invitation to guitarist Ivor Perry1 to come into the studio to join him, Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce for an impromptu recording session. The producer present for this session was Stephen Street, who later recalled the session and its aftermath:

“There was one session with Ivor Perry. Two days were booked at a studio in Wilesden [North London] and we did one day of that. The following day, which was a Sunday, I got a phone call from Andy Rourke saying that Morrissey had gone back to Manchester and that the session was cancelled. It was quite obvious to all concerned that it wasn’t going to work with Ivor Perry. There was a song recorded on that session called Bengali In Platforms, but it was nothing like the Bengali In Platforms that subsequently ended up on Viva Hate. In fact I don’t even remember Morrissey putting the vocal down in that session – it was just a title he had knocking around”.2

The lyrics of ‘Bengali In Platforms’ on this early version of the song were little more than a rough draft (perhaps nothing more than the title, as Street indicates), but supposedly bear some similarity to those that would appear in the finished version contained on Viva Hate. The music, however, was written by Ivor Perry and was completely different from the final product that Stephen Street would later co-write with Morrissey. Unfortunately, the author has not been successful in locating the recording of this early version of the song.

For his part, Ivor Perry appears to have distanced himself from any suggestion that he attended the recording session as a potential replacement for Johnny Marr, and that notwithstanding any thoughts to the contrary, that producer Street in fact sabotaged his efforts with Morrissey:

“I just want to set the record straight about this session as Stephen Street seems to have some kind of issue with me and in both books and here he puts forward the impression that I was somehow a disaster and should not have been in such talented company. some facts:

I never asked to do this session and was virtually press ganged by rough trade / [Geoff] Travis into doing it

Morrissey was both a friend and a fan of Easterhouse in general and my guitar playing in particular.

Morrissey chose the tunes we recorded from a selection I provided.

Street had recorded a record for my band that we rejected as we felt he had not captured the sound we were after (Heart of the City)

I also made it clear to all concerned that I wanted nothing to do with being considered as some kind of replacement for Johnny Marr. I had great respect for the Smith’s and knew that it was not going to be feasible to step into such a role and never wanted to. I just went in with an open mind and tried to record something worthwhile under the direction of Morrissey / Street as it was obviously an opportunity to work with a major talent.

It seems Stephen had his own demo selection ready and waiting and I did not feel he was trying particularly to make it work. Obviously it was a trying time for Morrissey and I do not blame him for leaving the session but I am just setting the record straight as I had respect for myself as a guitar player / songwriter and obviously Morrissey did too.

And as a final point we recorded two tracks, one of which was Bengali [In Platforms] and it did at least have a guide vocal as it was re-arranged on the fly to support the vocal”.3

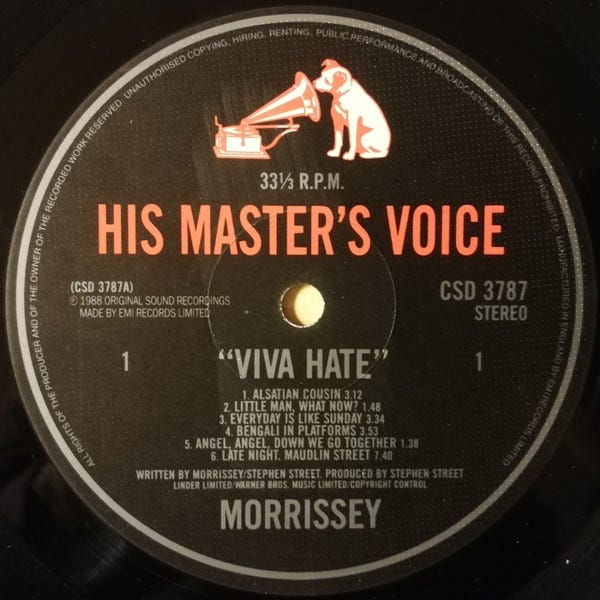

The definitive version of ‘Bengali In Platforms’ (with music provided by Stephen Street) was recorded in the Autumn of 1987 at Wool Hall Studios in Bath. In addition to being the producer, Street also acted as bassist. The other musicians on the recording were Vini Reilly (guitar) and Andrew Paresi (drums).

The UK music press, initially befuddled by the song, began to question Morrissey’s woke bona fides upon the release of ‘Bengali In Platforms’, whose lyrics they perceived as an indication that Morrissey possessed an opinion that was outside of the scope of “correct” thinking. While little more than a ripple in 1988, this perception has grown to tsunami proportions in the intervening decades. Indeed, in some circles the claim that Morrissey is racist is accepted doctrine that is closed to debate or reason4.

Case in point is a March 1988 interview wherein the issue of “Englishness” was touched upon. After some back and forth about the banalities of the subject, the interviewer turned their attention upon ‘Bengali In Platforms’ as the song relates to the matter of Englishness:

“On the same subject, there’s the line in “Bengali In Platforms”: ‘Shelve your Western plans/And understand/That life is hard enough when you belong here’. Don’t you think the song could easily be taken as condescending?"

“Yes…I do think it could be taken that way, and another journalist has said that it probably will. But it’s not being deliberately provocative. It’s just about people who, in order to be embraced or feel at home buy the most absurd English clothes.”5

In a later interview with another party, the matter was pursued in a decidedly pointed manner:

“While accusations of racism were spurious for ‘Panic’, revolving around Morrissey’s reasons for wanting to “Hang the DJ”, tactless lyricism on the album’s ‘Bengali In Platforms’ leaves it open to a racist interpretation.”

“Bob Geldof in Platforms you nearly said,” quips Morrissey, treating the issue with far more contempt than it deserves. Was it intended to have a double edge?”

“No, it still doesn’t, not at all. There are many people who are so obsessed with racism that one can’t mention the word Bengali; it instantly becomes a racist song, even if you’re saying, Bengali, marry me. But I still can’t see any silent racism there.”

“Not even with the line “Life is hard enough when you belong here”?

“Well, it is, isn’t it?”

“True, but that implies that Bengalis don’t belong here, which isn’t a very global view of the world.”

“In a sense it’s true. And I think that’s almost true for anybody. If you went to Yugoslavia tomorrow, you’d probably feel that you didn’t belong there.”6

Fast forward to 2007, and the subject of Englishness and identity was still at the fore for the New Musical Express, which queried Morrissey in detail on his thoughts on English identity and immigration. Morrissey adroitly parried the direction the interviewer took the conversation, explaining that

“[…] the British identity is very attractive. I grew up into it, and I find it quaint and very amusing. But England is a memory now. Other countries have held on to their basic identity, yet it seems to me that England has thrown it away…”

Not satisfied by this, the interviewer escalated the issue, pointing out that “There are people who are…very offended by some of your songs.”

“If you consider yourself to be a social writer then you have to stretch yourself and put certain topics on he table for discussion. And I think it’s also quite interesting to push people slightly and see how far they’ll go before they put their hands up and say ‘hang on’. But I can’t understand why anybody would be truly offended.”

“The line that a lot of people find hardest is from ‘Bengali In Platforms’: ‘Life is hard enough when you belong here.’”

“Yes but those people don’t know the protagonist in the song, who didn’t belong here. I wasn’t writing about those people [who are offended], it was someone else.”

“So why didn’t they belong?”

“Because they didn’t. Some people just don’t.”7

The article ends with the statement that Morrissey “won’t” realize that the language he uses about a ‘traditional’ England mirrors that used by the “crypto-facist BNP”8

Morrissey responded to NME’s article with a lawsuit for defamation for its implication that he was a racist, a suit that wasn’t settled until 2012 when the

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Morrissey, Ringleader of The Tormentors to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.