"Jeane"

The Smiths’ Outlier

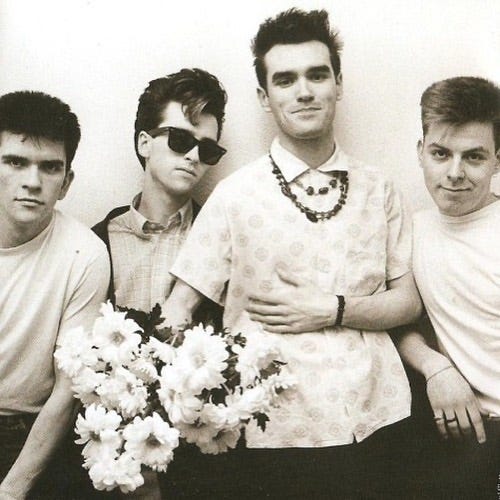

Among the earliest songs written by Messrs. Morrissey and Marr, “Jeane” dates back to 1982 and stands as a notable outlier in the band’s catalogue, both musically and lyrically.

If “How Soon Is Now?” is often cited as unrepresentative of the Smiths’ typical sound, then “Jeane” is its unspoken wallflower cousin: equally anomalous in its departure from the band’s defining elements.

There is little of Marr’s signature guitar work, and only a faint trace of Morrissey’s incisive irony and wit. Mike Joyce’s drumming is straightforward, taut and propulsive. Andy Rourke’s bass work is particularly notable on the track. His talent as an exceptional bassist shines through on “Jeane” with nimble, melodic playing that adds depth and energy. Listen to Andy’s isolated bass track in the attached link to appreciate his contribution to the song:

Overall, “Jeane” offers a raw, rough-hewn aesthetic - more a punk-inflected demo hastily assembled than a carefully crafted Smiths composition. Its lo-fi production, driving rhythm, and unvarnished tone set it apart, largely stripped of the elegance and nuance that would come to define much of the band’s work.

The song’s lyrics stand out in the Smiths' catalogue as among Morrissey’s most grounded and unadorned, presenting a bleak, almost brutally realistic portrait of domestic life steeped in penury:

“The low-life has lost its appeal / And I'm tired of walking these streets / To a room with its cupboards bare”

“There's ice on the sink where we bathe / So how can you call this home when you know it's a grave?”

The word “grave” serves as a chilling and apt metaphor for the emotional lifelessness he inhabits, while “The low-life has lost its appeal” signals a turning point - material deprivation is no longer romanticized or endured with working-class pride, but has become a burden too heavy to bear

.

The grim setting reflects not only economic hardship but also a deeper emotional desolation, as Morrissey confronts the absence of love and hope - and even the illusion of them:

“I'm not sure what happiness means / But I look in your eyes / And I know / That it isn't there”

“No heavenly choirs / Not for me and not for you”

Touchingly, Morrissey acknowledges his lover’s quiet dignity amid the degradation and squalor of their surroundings. Though he appears to admire Jeane’s fragile grace in the face of hardship, the moment is laced with bittersweet poignancy:

“But you still hold the reedy grace / As you tidy the place / But it will never be clean”

Although he acknowledges Jeane’s effort to maintain a semblance of order, he ultimately concedes its futility - their threadbare hovel, like the relationship, is beyond redemption.

Morrissey then employs the rather vintage phrase “cash on the nail”1 to evoke a longing for security, substance, and something dependable within the context of a romantic relationship. Yet this earnest desire is immediately undercut by disillusionment:

“It's just a fairy tale / And I don't believe in magic anymore”

This blunt dismissal of romantic idealism reveals a deep disenchantment. The belief in love’s transformative power - or in the promise of emotional security - has faded entirely. The fairy tale has turned to dust.

At the heart of the song lies its grim, repeated refrain: “We tried and we failed.” It encapsulates the song’s core message - not one of anger, blame, or even sorrow, but of quiet resignation. It is a subdued surrender to a plain truth: some things simply don’t work out, no matter how much effort is made.

Notwithstanding its status as an outlier, “Jeane” shares thematic ground with other early Smiths songs such as “Still Ill,” “These Things Take Time,” and even “Accept Yourself” - though it is more direct in its depiction of emotional and economic destitution.

While it may lack Johnny Marr’s melodic intricacy and Morrissey’s trademark ironic wit, the song remains firmly rooted in the latter’s familiar sensibility: working-class ennui, romantic pessimism, and a gift for uncovering lyrical poetry in the most mundane details. Indeed, “Jeane” is remarkable not despite its starkness, but because of it - offering an unsparing portrayal of a romantic relationship that is withered, resigned, and stripped of illusion.

The song was recorded in the summer of 1983 at London’s Elephant Studios with producer Troy Tate, alongside the tracks intended for the Smiths’ debut album. Unlike the material slated for the album - which was later re-recorded with producer John Porter that same summer - “Jeane” was never re-recorded.

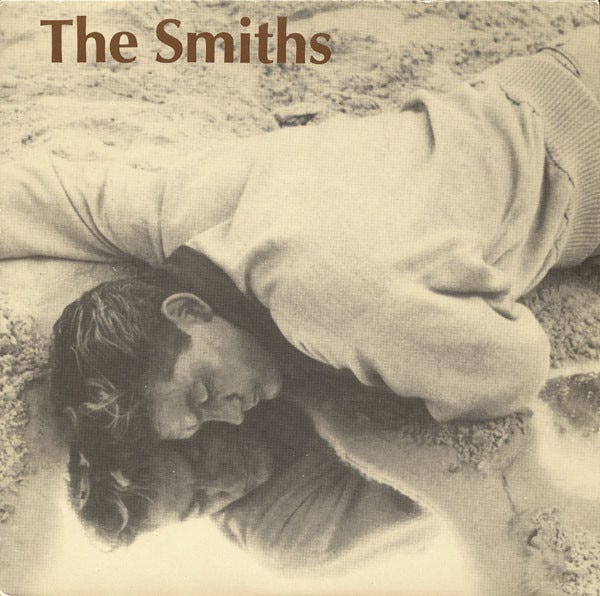

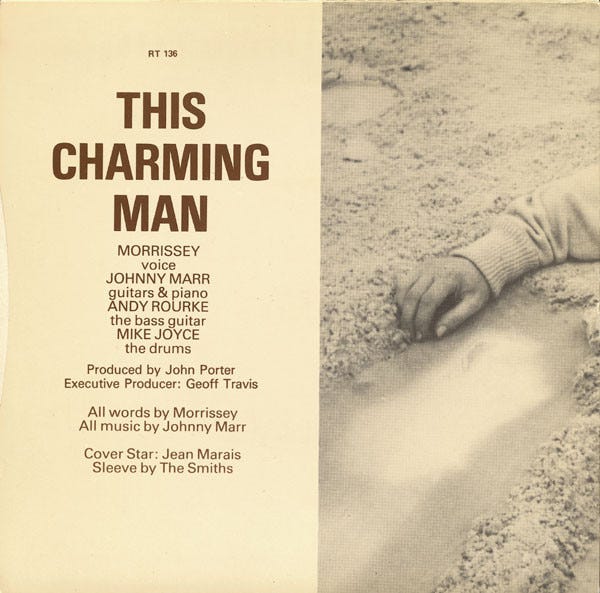

On October 31, 1983, “Jeane” was released as the B-side to the 7-inch version of the Smiths’ second single, “This Charming Man.” However, on the 12-inch edition, it was replaced by two different tracks: “Accept Yourself” and “Wonderful Woman.”

The runout on the 7-inch B-side is etched with “SLAP ME ON THE PATIO,” a line lifted from the Smiths’ track “Reel Around the Fountain.” It's a subtle nod to the band’s lyrical universe, and one of many cryptic etchings that became a signature feature of their vinyl releases.

Listen to “Jeane” here:

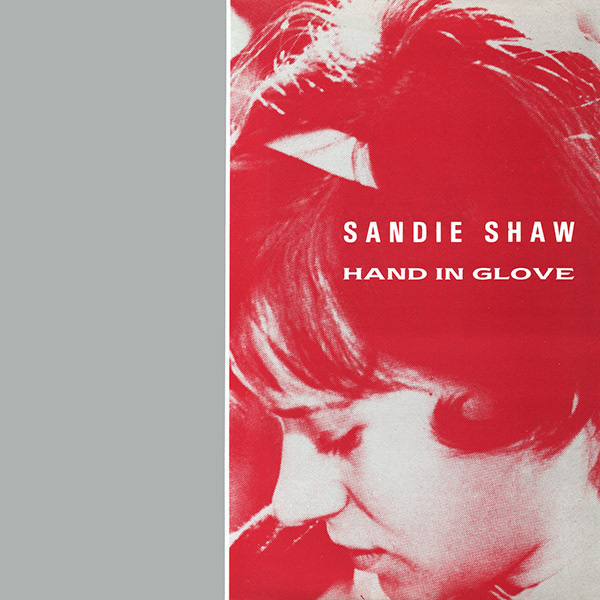

“Jeane” saw renewed life when English singer Sandie Shaw, in collaboration with the Smiths and producer John Porter, covered the song. Her version appeared as the B-side to her “Hand in Glove” single, released in April 1984.2

Listen to Shaw’s cover of “Jeane” (with Morrissey providing backing harmonics) here:

Another Sandie Shaw version (backed by Johnny only) was recorded for the BBC radio program Saturday Live, broadcast April 14, 1984.

“Jeane” was performed a total of 30 times (possibly more) by the Smiths, beginning with their third concert at the Hacienda in Manchester on February 4, 1983. Watch and listen to a rousing live version of the song from that performance, starting at 14:04 in the video linked here:

The phrase is almost certainly borrowed from Shelagh Delaney’s play The Lion in Love, where it appears in Act I as “paid cash on the nail.”

Sandie Shaw’s single featured three covers of Smiths songs: “Hand in Glove,” “I Don’t Owe You Anything,” and, of course, “Jeane.”

This song is a beauty, perhaps my all time favourite Smiths song, possibly originating from the time Johnny spent with Joe Moss's sunburst Gibson J45, it's a song that can be carried anywhere, packed into a satchel and slung over the shoulder, as shown with the definitive Sandie Shaw version it travels well.

The lyrics find an easy home in the sadness of an understanding of an end without bitterness, the sigh of acceptance provoked by the announcement that 'the low life has lost it's appeal' which is a quite beautiful and devastating entrance. It's a song that starts with an epitaph and ends with a keening, but there's levity and humour in the refrain as the chords skip along and away from the subject with a gladness in the surety of departure at a junction of destinies.