"We'll Let You Know"

We are the last truly British people you’ll ever know.

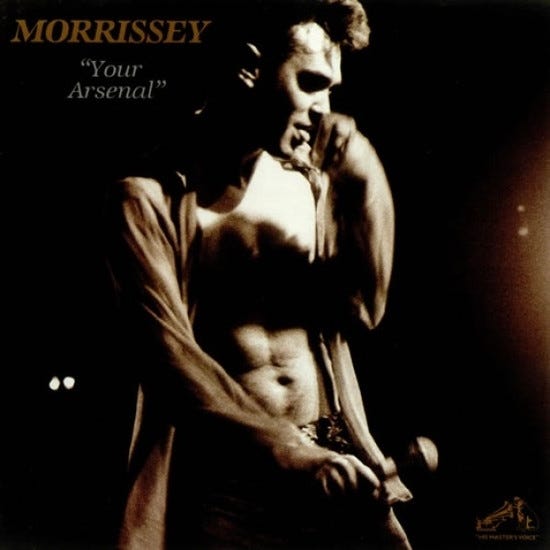

The third track on the Your Arsenal studio album, “We’ll Let You Know,” was recorded at Wool Hall Studios in March 1992. Produced by Mick Ronson, formerly of Bowie’s Spiders From Mars fame, the recording features Boz Boorer (guitar), Alain Whyte (guitar as well as co-writer of the track), Gary Day (bass), and Spencer Cobrin (drums).

“We’ll Let You Know” does not so much survey the world of British football hooliganism as frame it, situating its violence, loyalty, and pronounced camaraderie within the broader meditation on English identity that Morrissey delves into on the Your Arsenal album.

It is necessary to examine what “Englishness” means in relation to Morrissey himself in order to give “We’ll Let You Know” proper context, which is critical to understanding not just the song, but how it is that the child of two Irish immigrants would be so inclined to survey the topic of football hooliganism.

It is hardly a revelation to fans that Morrissey has long described himself as possessing a “split identity,” having been born and raised in England to working-class Irish immigrant parents from Dublin1. Seen through this lens, one can (hopefully) better understand Morrissey’s perspective on the vanishing England of his youth, even as he sharply critiques many aspects of it, as evidenced in the lyrics of more than a few Smiths songs.

While football hooliganism is not exclusive to Britain, it is an especially notable feature of its working-class culture, and therefore an aspect of it Morrissey would have more than a passing familiarity with. Consequently, it is of little surprise that Morrissey should delve into this particular strand of ‘Englishness’ in the lyrics of “We’ll Let You Know.” Notably, there is a palpable streak of empathy in how he handles the topic, which he took pains to explain in some detail in a 1992 interview:

Q: “The song We’ll Let You Know seems to sympathise with football hooligans. Is this the case?” Morrissey: “I understand the level of patriotism, the level of frustration and the level of jubilance. I understand the overall character. I understand their aggression and I understand why it must be released.” Q: “Are you suggesting you’ve had first hand experience of this?” Morrissey: “I’m not a football hooligan if that’s the question. You might be surprised by that. But I just understand the character. I just do. I’ve got a computer at home for such things.” Q: “Is this not just Morrissey picking up on another controversial theme?” Morrissey: “It’s hard to believe but no, it isn’t. I can’t fully explain. When I see reports on the television about hooliganism in Sweden and Denmark or somewhere I’m actually amused. Is that a horrible thing to say?” Q: “It could be construed as such.” Morrissey: “As long as people don’t die, I am amused.”2

From a strictly historical perspective, football hooliganism emerged in Britain in the 1960’s. By the 1970s and 80s factors such as unemployment and alienation were seen as contributing to its expansion. Hooliganism functions as a subculture where individuals, often young men from working-class backgrounds who may feel socially excluded or politically powerless, find a strong sense of community and brotherhood that is otherwise not available to them. Loyalty to their “firm” (individual hooligan group) and club becomes a primary aspect of their identity.

Beginning with its title, the lyrics of “We’ll Let You Know” speak to the listener with a collective voice that is bleak, defensive, and thoroughly self-aware. The speakers acknowledge their own balefulness and aggression with a distinctly British mix of irony and resignation, while distrusting outside judgment (“only if you’re really interested”).

Rather than being an inherent nature of their milieux, violence is presented in the song as a product of environment…the stadium, the crowd, the ritual (“it’s the turnstiles that make us hostile”). Their chants, which are both taunting and provocative, are shown as a sort of performative masculinity, their aggressive behavior as much a shield against vulnerability as it is to assert dominance.

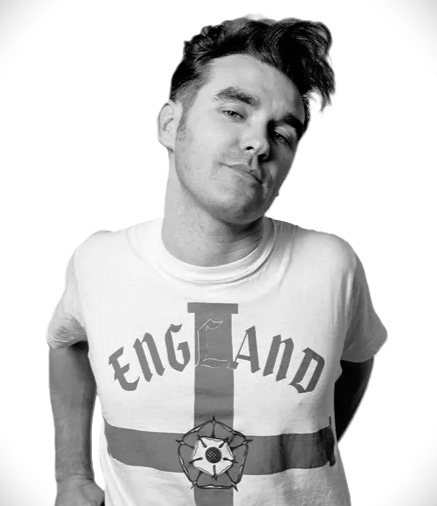

Perhaps the most striking aspect of “We’ll Let You Know” is its claim to be “the last truly British people,” a vaguely proud yet poignant assertion that springs directly from Morrissey’s exploration of fin-de-siècle anxieties concerning identity, class, and cultural change in the UK in general, and England in particular. The song’s final line, “You’ll never, never want to know,” underscores a sense of permanent alienation, reflecting a belief that modern, progressive Britain does not wish to understand this rough-edged, increasingly isolated, yet enduring version of itself.

“We’ll Let You Know” opens with melodic guitar that is notably muted, paired with a subdued rhythm section that is marked by martial-style drumming. Morrissey’s opening vocals are restrained. In under two minutes, the arrangement shifts into a prolonged middle section that gradually gathers tempo, driven to a large degree by atmospheric sounds and menacing audio samples that evoke chaos and unease. The three-plus-minute instrumental bridge is similar in structure to Morrissey’s “Black Eyed Susan” and “Southpaw”, though in this instance it features muted guitars, percussion, and crowd-like chanting, conjuring the ritualistic energy of a stadium or tribal gathering. Towards the end of this section, the chanting comes into the fore just before before Morrissey’s vocals return with heightened earnestness, as if pleading with the listener. The outro introduces a fife-like woodwind instrument, lending an archaic, almost ceremonial quality that contrasts with the song’s modern aggression, reinforcing its themes of ritualized identity and collective tension.

The song’s placement on the Your Arsenal album - sandwiched between “Glamorous Glue,” a weary lament for a culture losing its cohesion, and “The National Front Disco,” a portrait of a young man drifting into extremist nationalism - is striking as it is telling. Together, these three tracks carve out a thematic space distinct from the rest of the album: a small musical triptych regarding working-class pathos and the shifting social landscape of Morrissey’s England.3

Apart from its initial issue on Your Arsenal in July 1992, the song appears on several Morrissey releases. It features on the live album Beethoven Was Deaf, released on 10 May 1993, which was recorded at The Zenith in Paris on 22 December 1992. The song was also included in the 20th anniversary remastered edition of the Vauxhall and I album, released in May 2014. This reissue came with a bonus CD containing live tracks from Morrissey’s 26 February 1995 concert at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London, including “We’ll Let You Know.”

In addition, the song appears on the 1995 compilation album World of Morrissey and on the 1996 concert video Introducing Morrissey, initially released on VHS and later on DVD in 2014. This recording was taken from Morrissey’s concert at the Empress Ballroom, part of the Winter Gardens entertainment complex in Blackpool, England, on 8 February 1995.

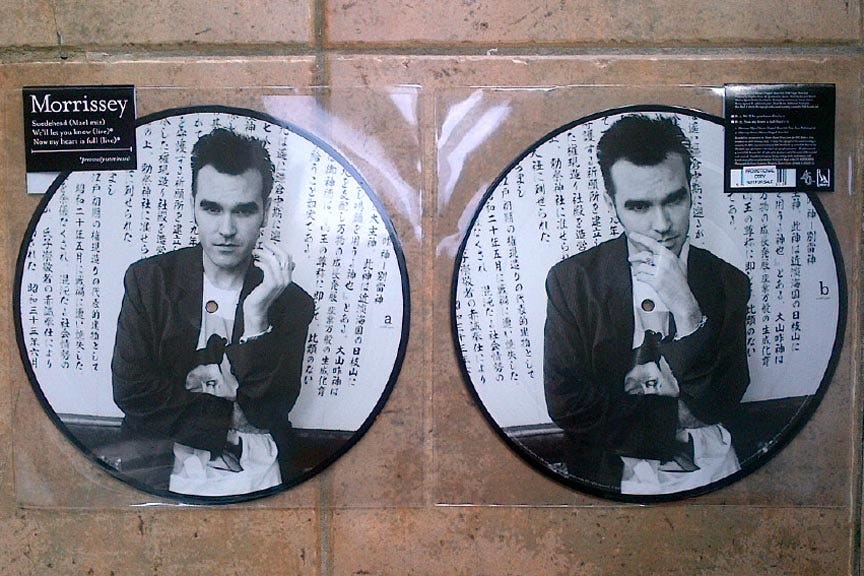

On Record Store Day in 2012 (21 April), a live version of the song, recorded at the 26 February 1995 Theatre Royal concert in London, was featured on the B-side of a limited edition 10-inch picture disc of the Mael Mix4 of “Suedehead”.

This duality is explored more explicitly in “Irish Blood, English Heart,” wherein Morrissey directly confronts his position as an Englishman of Irish descent.

Adrian Deevoy, “Ooh I Say: The Q Interview,” Q, September 1992.

The apogee of Morrissey’s misconstrued foray into overtly political themes in his early 1990s music was capped by his live performance at the Madstock Festival in Finsbury Park, London, in August 1992, where he used a backdrop featuring a photograph of two skinhead girls. During his performance of “Glamorous Glue,” he displayed a Union Jack and at times wrapped himself in the flag. The juxtaposition of the Union Jack with the backdrop of the two skinhead girls prompted the NME to dedicate its front cover and a staggering 6,000-word article, titled “This Alarming Man,” to the question of whether Morrissey had gone too far at Madstock.

This incident highlights the perception that his songs and associated performative elements amounted to an endorsement of what some considered extremism, and were therefore offensive. Over the years, this perception has metastasized to the point where, in many circles, Morrissey is seen as antithetical to “mainstream” values - a gadfly whose music, both with the Smiths and as a solo artist, must be accompanied by a cautionary label lest listeners be painted with the same brush as he.

At 3:35, this version of the mix was edited down from the original 6:37 version, which was released in 2006.